Sony TVs made by TCL: best case scenario, worst case scenario

What can go right and what could just as easily go wrong for consumers in the context of this joint venture

KOSTAS FARKONAS

PublishED: January 21, 2026

So this happened: Sony – after years of struggling to remain competitive in the TV set product category against the likes of Samsung, LG, TCL and HiSense – is ready to basically offload its entire home entertainment devices business on to a new company run by TCL. While both Sony and TCL are careful to call this “a joint venture” and “a strategic partnership”, what this actually means is that the Japanese company won’t be considered a TV and home audio manufacturer anymore: more like a licensor whose patents, know-how and technical expertise is used on products made by another manufacturer.

If the deal is finalized and approved as planned, it will be the end of an era for Sony Electronics. It most probably won’t be its only exit from a consumer product category to happen in the near future, too: the writing has been on the wall ever since Sony’s top management confirmed to investors that it’s changing direction, focusing more on mainstream entertainment content and services than on devices.

In some markets it can’t really do that without new hardware that works as a reason to buy new content, as is the case with the PlayStation. In other markets, though, especially ones where Sony has been losing money for many years – such as TVs, disc players, home audio and smartphones – that is not the case, hence the company’s decision to move forward with this joint venture.

Sony is changing direction as a whole, focusing on content and services rather than on devices – hence this TCL partnership.

What does all of this actually mean for consumers, though? Nobody can predict with absolute certainty – not even Sony or TCL executives – how it will all play out in the long term. Based on current information and similar past cases, though, one can outline a best-case scenario and a worst-case scenario for this partnership: what consumers would stand to gain if this joint venture works with their interests in mind… and what they would stand to lose if both companies only focus on short-term profit. Here’s how each scenario would look like.

Best case scenario: the Sony DNA survives, we get great TVs – maybe at better prices

It really is worth noting that this “strategic partnership” goes way beyond what Sony has been doing over the last decade: that is, to purchase and use panels made by other manufacturers in order to put its own TVs together. Sony did that, but did everything else itself, which made those TVs true Sony TVs. In the context of this joint venture TCL is responsible for almost everything: develop the platform the new TVs will be based on after 2027, provide the panels and manufacture the TV sets, as well as take care of all logistics, sales and after-sales support.

TCL will be running most operations and, as a result, it will be taking way more risks than Sony does. So what will the latter be contributing to this partnership? Hopefully, best case scenario, five different things. One: the new TV sets’ design, as Sony has always been good at this and it would definitely do a much better job at retaining the premium character of its products than TCL would. Two: its extensive, proven know-how in terms of picture and audio processing algorithms, which are still unmatched in this industry.

Three: the software these TVs will run on, as Sony usually does a better job leveraging Android TV than TCL does. Four: marketing, as Sony is more experienced at illustrating the advantages of its products and has more long-standing relationships with the press or creators than TCL. Five: screen quality control, through a specific, selective Sony procedure meant to keep Bravia screens within certain manufacturing tolerance levels.

This scenario would ensure that the TV sets released by this new Sony/TCL joint venture would retain enough of Sony’s DNA to attract its traditional fans’ interest. They’d be good-looking, quality-checked, well-performing TVs not lacking in functionality or software support, marketed at Sony’s traditional crowd: consumers who value picture quality above all else, love modern aesthetics and own other Sony products too (with which Sony TVs can work well through software).

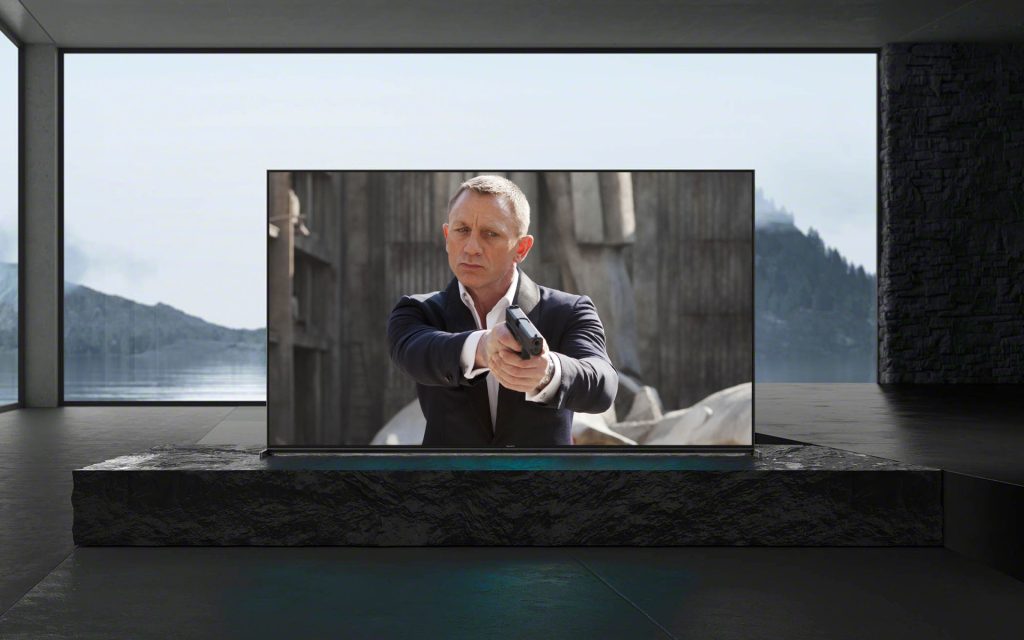

If these TCL-made TVs retain enough of Sony’s DNA, they will probably be able to attract the interest of BRAVIA fans anew.

In that scenario – if all five possible Sony contributions are made – the “Sony” label on these TV sets would be earned even if their overall build quality takes a hit (in the event of TCL choosing to cut corners at the manufacturing stage). Sony and TCL could continue to sell these new Bravia TVs as premium products… or they could choose to price them more aggressively and in line with what e.g. Samsung or LG will be releasing at that time frame. It’s your truly’s opinion that – with the economies of scale achieved and all the other expenses saved by the consolidated operations of this new joint venture – these new TVs could easily be priced in a competitive but sustainable, profitable way.

Worst case scenario: the Sony DNA is lost, we get worse TVs – maybe at premium prices

Not a single person interested in cinematic picture quality and healthy market competition would not like to see the best case scenario come true, there’s always a chance that a very different scenario plays out. In that, Sony has already decided it does not really care enough to have its name associated with some the best TVs in the world anymore, in which case it basically rents out its valuable brand and that of the acclaimed BRAVIA lines to TCL so that both can just be slapped onto decidedly not as-high-quality TV sets as before.

Those would just be rebranded TCL TV sets – designed, built, sold and supported without any Sony involvement – that could even be sold at Sony pricing despite the expected TCL corner-cutting. Crucially, none of those sets would come with the “special sauce” – the image and sound processing algorithms – that made a BRAVIA TV, a BRAVIA TV. This could go on for a few years until the BRAVIA brand would lose all meaning and value, at which point it would be silently killed off or sold to another manufacturer to try and make some money out of.

If that sounds overly dramatic and thus unlikely, here are two examples to consider. One, hitting closer to home, is the VAIO brand, Sony’s line of computers which was sold off to Japan Industrial Partners in 2014. VAIO computers were quite popular with Sony fans for a decade, but it quickly became apparent that the new, JIP models would retain practically none of the VAIO DNA, so sales tanked. Japanese retailer Nojima acquired JIP last year and now VAIO is essentially a single tech-supermarket product.

There’s always the possibility that this joint venture is nothing but a dignified fadeout for the acclaimed BRAVIA brand.

The other example is obviously that of Philips, which sold off its TV business to TPV back in 2012 and gradually stepped back from any meaningful involvement – leading to what can only be called an anemic market presence nowadays, with just a handful of TV models released each year mainly for the European market.

The most likely scenario: somewhere between the best and worst one

There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that Sony stepping away from a number of product categories it’s been losing money on, for many years, was inevitable. The way a company like this one exits a consumer market it once dominated, though, is important in terms of optics and, as a result, of future sales too. It’s too early to say whether this joint venture with TCL was a smart move, a big mistake or a forced choice – the very fact that this development will be part of every discussion about Sony TVs from now on, is telling.

At the end of the day, once reality sets in, this strategic partnership may prove to not be brilliant or catastrophic for Sony and the BRAVIA brand name: we may very well land somewhere between the best case scenario and the worst case scenario, depending on the terms of this deal and how involved Sony actually intends to be with these products after spring 2027. The new, 2028 TCL-made BRAVIA TVs seem as likely to be major disappointments as true game-changers right now. Yes, it really could go either way. Too many variables, too early to tell.

What happens in the meantime, of course, is anyone’s guess: consumers are often unpredictable, sometimes choosing to support certain companies’ decisions and efforts, other times choosing to turn their backs and spend their money on competing products. Sony fans have always been among the most loyal in the home entertainment market, but even they might think twice to invest in a 2026 or 2027 BRAVIA TV if it’s TCL, not Sony, they’d be expecting software support from.

In the same context, yours truly is extremely curious to see what traditional BRAVIA fans – the aforementioned crowd that puts cinematic picture quality above all else – will think of the first TCL-made Sony TV sets, especially since they will almost certainly be Mini-LED and RGB-LED, not OLED models. Interesting times ahead, no?